Fire and Water

May 06, 2012Posted by Forno BravoI have to admit right up front that the next couple of things I am going to say are really (really) obvious. But bear with me, I might make a little bit of sense and find a bit of insight. Maybe.

1. Dry firewood, with less than 20% moisture burns fast and better and is far easier split than damp wood.

2. Firewood that has been stored properly, and not left exposed to winter rain/summer dry out cycle performs much better than wood left out to in the rain.

Yes, and if I keep this up much longer, I am going to start talking about flossing, so I’ll stop.

What really happened is that the moisture gauge I am testing out for my firewood arrived yesterday, and I had a lot of fun using it today. As a little bit of background, I had a large delivery of mixed firewood a couple of years ago—mostly oak and madrone. I stacked the wood on the north-facing side of the house and covered it with a tarp while also filling the wood storage areas under my pizza oven and fireplace. Flash forward to today, and I have three grades of wood. The wood stored under my pizza oven (which I have never rotated out because it looks so nice) is perfectly seasoned with a moisture content in the mid-high teens, and it burns wonderfully.

The wood under the tarp is more of a mixed bag. First, the wind has blown the tarp off the wood in various places, leaving it exposed to the elements. The wood in these spots has a water content of 25%+, making it hard to work with and slow to burn. I am writing this in early May, and we have not had a lot of rain recently. The wood under the tarp is better, though not as good as the wood the has been completely dry under the oven.

I’ve written before about the interaction between water and heat and fire. Remember that water turns to steam at 212ºF, and that the volume of steam is 1600 times greater than water—which explains how you can ruin a pizza oven if you bring it up to pizza baking temperature without properly curing, or drying it out. From the perspective of firewood, there is a similar, though much less important dynamic. For firewood with more than 25% moisture content, the combustion process involves first baking, or boiling, that water out of the wood before the wood itself will combust—a process that consumes some of the BTUs from your fire and your oven. Wet wood actually makes a negative contribution to your oven before it is baked dry and starts to burn.

The photo below tried to capture this dynamic, where I added two pieces of wood to a good size fire. The 16% wood on the left quickly caught fire, while the 26% wood on the right put out grey smoke for a while, and then eventually emitted boiling water out of the end for a long time, before finally catching fire.

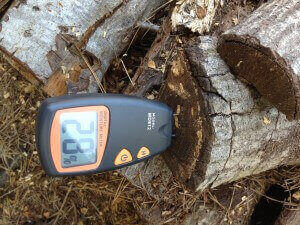

Finally, I wanted to review my new $20 moisture gauge. The gadget itself works well; it’s small, inexpensive, fast and easy to read. So while it isn’t as interesting, or useful, as an infrared thermometer for your oven, and you will not use it nearly as much, I still would recommend that you buy one. You can use it when you are wood shopping, or accepting (or rejecting) a delivery of wood, and you can test your wood a couple of times a year—say after the winter rain and in the summer and fall. If you are having trouble building good fires or bringing your oven up to temperature, knowing the condition of your wood is definitely helpful. If you own a wood fired catering oven or food truck, or a wood-fired oven for your restaurant, you should definitely have one.

Me, I’m off to bake some bread and blog a little more on oven curing and dry out.