Interview with Lou Bank: Mezcal as S.A.C.R.E.D.

Note from Peter: I met Lou Bank at the Fermentation Festival in Reedsburg, Wisconsin, where he put on an amazing dinner using all sorts of fermented foods (plenty of kimchee!!) and local pork and grains, but mainly it was a celebration, and “Master Class,” in mezcal. We tasted five different rare, artisan examples as Lou explained all the nuances. I’m no expert in mezcal spirit beverages, or tequila, it’s most well known version, but I left that evening feeling like I had taken a major step in understanding and appreciating all the skill, craft, and science in this very specialized and endangered art form. I won’t say more but, rather, will let Lou tell you himself, as he graciously agreed to meet with me and share hs passion and sense of mission with all of our followers. We say that Pizza Quest is not just about pizza but, rather a celebration of artisanship wherever we find it and this is a great example of someone with a burning passion, a fire in his belly, notably for mezcal but for making a difference in the lives of the people he has come to know in Mexico. Enjoy!!

PQ (Peter): Lou, thank you so much for doing this interview. You are so passionate about your work with the agave community in Mexico, but this isn’t your day job, more like a labor of love. Can you share with our readers how you got into this and what exactly your group, S.A.C.R.E.D., is?

Papalome Agave

Lou: Thanks for the opportunity to talk about Mexico and agave, Peter! S.A.C.R.E.D. is an acronym — it stands for Saving Agave for Culture, Recreation, Education, and Development. That’s a nutshell description of what I’m doing with S.A.C.R.E.D. The longer description is that I’m attempting to improve the quality of life for children in rural Mexico by leveraging the truly unique, handcrafted spirits they’re making in these towns.

In the early 2000s, I worked for Rogue Ales. One of my assignments was to launch the brewery’s “craft” distillery — both obtain federal approval to distill and also oversee production of the first craft spirits. So I thought I knew what distilling was supposed to look like.

Fast-forward to October 2008, and my wife and I are looking to leave Chicago for a week while we’re being moved out of one house and into another. At that point, I’d been drinking mezcal for a couple years; I fell in love with the Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos through the amazing annual exhibit at the National Museum of Mexican Art, and my little sister had spent some time in Oaxaca — the birthing ground of both mezcal and Dia de los Muertos — and had been lobbying for us to visit for years. So, we went.

On that first, brief trip, we fell in love with Oaxaca. Through a series of odd coincidences — and I’ve since learned that everything related to Oaxaca and agave spirits, including meeting you, Peter, produces odd coincidences — we met Don Lorenzo Angeles, the fifth-generation maestro behind Mezcal Real Minero. Don Lorenzo invited us to tour his palenque (distillery), which we did the next year.

I’d expected that visit to the Real Minero palenque in Santa Catarina Minas, Oaxaca, to be a standard one-hour tour. Instead, Don Lorenzo’s son, Eduardo “Lalo” Angeles, led us on an eight-hour crash course on traditional and artisanal agave spirits. We walked from the fields, where they were farming agave, to the mountains where they harvest agave varietals from the wild. We saw the water sources, met the mezcaleros working the palenque, and were introduced to the truly hands-on, inefficient process of making these amazing spirits.

So that’s the first piece of it — how I became interested in the spirits. The second piece is the quality-of-life programs in these towns. Since 1999, I’ve spent the majority of my time working in the nonprofit field. Even at Rogue Brewery, the reason Jack Joyce hired me initially is because of my connections to nonprofits. He and the team that launched Rogue were also the marketing team that launched Nike back in the 1970s. They didn’t see the point in spending money on advertising unless you had a seven-figure budget — instead, they thought partnering with nonprofits was a way to build your brand. If you volunteer for the Oregon Humane Society and you see that they are hosting fundraisers at the Rogue pubs and pouring Rogue beers at their other fundraisers, Jack figured you’d be more likely to drink Rogue when you went out to a bar or restaurant.

Eduardo Angeles in his agave field.

PQ: Very clever marketing, and a win-win for everyone!!

Lou: Right! So, anyway, nonprofits and volunteerism have been in my life for decades. One of those nonprofits is StoryBus, a children’s museum on wheels that visits pre-k and kindergarten classrooms in Chicago’s low-income neighborhoods. Lalo knew about StoryBus, but assumed it was a bookmobile. He asked me if I would help build a bookmobile for his community, because he wanted the next generation to have a better life than he had and he knew that wouldn’t happen unless they learned to read.

Anyone who has ever visited Mexico knows that almost everything is less expensive there. But not books. A book you’d pay $25 for here would sell for $40 in Mexico, and in these rural communities, that can amount to as much as two weeks’ pay for the average citizen. So there are simply no books in these towns.

Lalo’s sister, Graciela, took over the library project — she morphed it into a brick-and-mortar learning complex with a library at its center, and it’s now almost complete. We’ve helped raise funds for the library, but the heavy lifting has been done by Sabra Dios, an artisanal spirits store in Mexico City.

Lalo is now maestro of his own palenque, Mezcal Lalocura, while Graciela runs Real Minero. But Lalo has his own community-development projects: he helps run a greenhouse that supplies baby agave plants to people in the community and replants agave in the wild, and he devised a system that captures rain water in reservoirs around the community that ensure they won’t suffer during times of drought. The fund-raising I do gets split primarily between these three projects: the library, the greenhouse, and the water reservoir in Santa Catarina Minas, Oaxaca.

Eduardo Angeles’s water reservoir project, to collect the rain, which comes infrequently.

PQ: Can you describe what the process is, from agave to mezcal, and how is mezcal different from tequila?

Lou: Yeah, happily, but I’ll say upfront that I’m going to be rounding a lot of “rough edges.” You could write a book explaining the differences — and Sarah Bowen has done exactly that, with her fantastic Divided Spirits — and I feel like I already chewed your ear off with the answer to your first question.

PQ: No problem, I’m loving it — this is amazing information and something I think many of our readers will want to know about!

Lou: So, the general term I use for the category is “agave spirits” or “destilado de agave.” Most people will use the word “mezcal” for the category, because that’s the word that’s been used for literally hundreds of years to describe spirits that were made by fermenting and distilling any one of the 200 to 300 varieties of agave that grow in Mexico.

But just before the turn of the century, Mexico established a “Denomination of Origin” for “mezcal” — that’s an international agreement that, in essence, gives trademark to a country for a specific product. Champagne, for instance, is a “Denomination of Origin” controlled by France, and to qualify to use that word on your product, you have to follow the rules established by France for the manufacture of that product. One of those rules includes the geographical location where it’s made.

The same is true now of mezcal. Mexico controls the word and has put into place rules that govern what can be called mezcal. To qualify to be called mezcal, a spirit must be distilled from a fermented agave by a certified palenque in a defined region of Mexico.

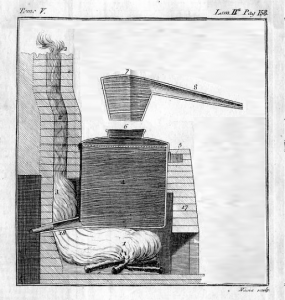

An old mezcal still from a book dating to 1849.

Tequila is very similar. To qualify to be called tequila, a spirit must be distilled from a fermented agave by a certified distillery in a defined region of Mexico. The difference between the two is that regions are different and in the case of tequila, the only agave they are allowed to use is the blue weber agave.

The shame is, the purpose of the international concept of “Denomination of Origin” [DO] is to protect cultural heritage, but Mexico isn’t using the DO’s to do anything like that. In fact, the tequila and mezcal DO’s at best encourage the maestros making them to turn away from the process that makes the spirits so special and so delicious and, at worst, literally requires them to turn their back on the ancestral nature of the spirit.

There is a cost — a significant cost, in terms of relative incomes in rural Mexico — to certifying your distillery and then certifying each batch of spirits coming out of that distillery. The per-batch cost doesn’t change much, based on the size of the batch, so a 200-liter batch can cost as much as a 2,000-liter batch, so the cost incentives are to make larger batches — and to make larger batches, you often need to introduce efficiencies into the fermentation and distillation processes, and those efficiencies take a lot of flavor out of the final product.

PQ: As a novice taster, I had no idea there were so many different types of agave cacti, and also how many different ways it can be roasted and distilled, whether in earth ovens, in wood, in clay, or even plastic. The different flavor profiles seem to be as dramatically distinct and smoky as Scotch. How do these small, artisan mescal producers differ from the mainstream, large volume companies?

Lou: We talk a lot about “craft” spirits in the US. And, in fact, as I mentioned, I started one of the first “craft” distilleries in this country. But the plain truth is that there is only one true craft spirits movement, it is in Mexico, and it started hundreds of years ago.

A wooden log “fermenter”

If you travel through rural Mexico, you will find fifth-, sixth-, and seventh-generation maestros who are making their spirits in the same way that their grandfathers, great-grandfathers, and older forebearers did. They harvest agave plants that took at least four years and as much as forty years to reach maturity — that being the point at which the plant has produced it’s maximum sugar capacity.

Every alcoholic beverage we drink stems from a sugar source. Beer comes from malted grains; rum comes from cane sugar; wine from grapes. These sugar sources take a maximum of six months to reach harvest. Six months! Compared to four years for Blue Agave, the youngest agave that can be harvested. So when we talk about terroir — the notion that something tastes like the place from which it came — we have to ask, what’s going to taste more like the place it comes from? The grapes that were on the vine for six months? Or the agave that was in the ground for four years? Fourteen years? Forty years?

So, these maestros in rural Mexico harvest these long-growth agave plants, and then roast them in an earthen oven — literally a stone-lined hole in the ground. They cover the roasting agave, much the way you would a pig or goat that is cooked underground. They then mill the roasted agave either using a machete and large wooden mallet (that looks like Fred Flintstone’s softball bat), or with an oxen-drawn stone wheel, or, the more modern way, with what in essence is a wood-chipper.

An earthen oven at the Lalocura distillery.

The roasted agave is then fermented. This is done most commonly in these communities in an open-air, wooden barrel, but I have also seen bull skins and hollowed logs used as fermenters, and have heard of fermenters made from stones that have been ground down into pools.

Now, I know all of this sounds very romantic, but this method of fermentation isn’t just fetish — it’s important to the process. Those sugars I mentioned? For this agave to be converted into alcohol, the sugars need to be consumed by yeast, which will spit out CO2 and alcohol. The practice of open-air fermentation is rare because our world is full of wild yeasts, and all yeasts impart different flavors to their ferments. Most alcohol fermentation is practiced in a sealed system, away from oxygen, so that the wild yeasts can’t access the sugars — a specific yeast that imparts a specific flavor will be introduced by the fermenter, kind of like an arranged marriage. To go back to that notion of terroir, the agave in these communities is being fermented via the natural yeasts present in the communities. By contrast, brewers in Chicago are using yeasts that have been cultivated in Belgium.

Additionally, open-air fermentation presents a second challenge. As I said, the yeast eats the sugar and spits out alcohol and CO2. That CO2 creates a natural barrier that prevents acetic acid bacteria which, like yeast, is all around us, doing what it wants to do, which is eat sugar and alcohol and spit out acetic acid, also known as vinegar. So imagine you have an open-air barrel of fermenting Arroqueno agave. Those agave took 20 years to reach harvest age. You lovingly roasted them in an open-air pit and milled them with your hands using a machete and a wooden mallet. That rare agave is now fermenting in your barrel, courtesy of those wild yeasts, and … you get a cold. When that fermentation slows down, and that CO2 barrier dissipates, the acetic acid bacteria swoops in and turns your ferment into — vinegar! A delicious salad dressing, sure, but no one is buying rare agave salad dressing, so you’re out time and money.

Roasted agave, ready to be shredded and fermented.

A bullskin fermenter — hey this is more craft than lab science, and a lot can go wrong. No one wants to wait 14 to 18 years for the agave to grow and then ruin it during fermentation. That’s some serious pressure and requires great skill.

The maestro in these communities will watch their ferments closely and distill as soon as they feel the fermentation has slowed down sufficiently that the CO2 layer is gone. That distillation process is also unique. You’ve probably seen those giant copper stills they use to distill almost everything else you’ve ever had in a bar. These stills do the simple job of heating up your ferment to the right temperature to separate alcohol from water.

Basically, alcohol starts to boil at 173 degrees; water boils at 212. So you want your still somewhere between those two numbers in order to turn your alcohol into vapor — that vapor will float up, run through some lines that divert it from the main column, cool it back into a liquid, and drop it, high proof, into a receiving container. But that only happens when you keep your still’s temperature between 173 and 212.

In the stills that (almost) everyone else uses, they simply dial in the temperature they want and hit start — like you would with a microwave oven. But in these towns in rural Mexico, the maestros achieve that same separation of water and alcohol by heating the ferment in a wood-fired pot still — sometimes made from copper, sometimes made from clay. The attention required to maintain the right temperature is significant and, I would argue, the variation in temperature leads to some of the variation in flavor in the distillate.

Additionally, because the stills are wood-fired, the maestros have to do much smaller batches. You can’t consistently heat a large copper still using fire as a fuel. And I don’t think you could physically make a clay still at larger than 50 liters.

There are additional steps that these maestros in rural Mexico take to make their artisanal spirits, but,I think I’ve already gone on too long. If you want to know more, read Sarah’s book. Or join me in Oaxaca and I’ll show you the process.

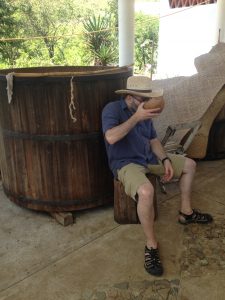

Here’s Lou sampling in the palenque. He loves bringing folks here for tours.

PQ: That sounds like fun!

Lou: For sure. But the point I’m trying to make, in answer to your question, Peter, is this: There are agave spirits that are certified as mezcal that are made in this pain-staking, artisanal process. There are also agave spirits that are certified as mezcal that have seen none of these steps in the process, that are made the same way an industrial vodka is made. To my knowledge, there are no agave spirits certified as tequila that are made in this artisanal process, but there are a couple of brands that I understand are using some of these artisanal steps — usually roasting the agave using wood fire or milling the roasted agave using an oxen-drawn stone wheel.

Most labels don’t have the space to illustrate the complete process, so, either you know how the spirit is made or you don’t. Bottom line: taste it, and if you like it, drink more!

PQ: What are some of the other challenges facing the growers and mezcaleros?

Lou: Well, on the growing side, think about all the challenges facing farmers here in the USA: rising labor costs, rising land costs, climate change, and so on. Now add to that the product you’re growing has a harvest cycle of at least four years. Most farmers will only grow Blue Weber agave or Espadin agave. The former will generally take four to six years to reach harvest age; the latter, six to eight. It’s hard enough for farmers here to predict demand for their crops within a maximum six-month cycle. Can you imagine trying to predict what demand will be in eight years? And carrying your expenses and holding your land for that long?

This is why so many mezcals are made from wild agave. But that presents yet another challenge. When you harvest the agave, you eliminate the possibility of that plant generating offspring — you harvest before it can expend its sugars to produce seeds. Now, because that agave has grown in the wild, no one is tracking it. There are no cycle-sheets that direct maestros to harvest this Tepextate — an agave that takes 35 to 40 years to reach maturity — but to leave that Tepextate, so that there will be seeds that will ensure we have another crop of Tepextate in another forty years.

Espadin Agave — it takes time to replace them as they are harvested.

This is the reason S.A.C.R.E.D. directs money to the greenhouse in Santa Catarina Minas — we want to be sure we are funding the replanting of more agave than we are drinking. This is primarily because we want to be sure these communities always have access to the agave they need to continue this art form, but also because agave plants take an enormous amount of carbon out of the atmosphere. This is an environmental issue, too, see?

For the maestros, the biggest challenges, I think, are the physical demands of the job, which is why some of them have moved to using a mechanical wood chipper to mill the roasted agave, since that particular step takes an enormous toll on the body. The temptation to bring efficiencies into the fermentation and distillation process, which could bring more money to their families and ensure a better life for their children; and the threat of disappearing agave, which, as demand for these spirits grows, can lead to friction among neighbors.

PQ: Are there other challenges too?

Lou: Another big challenge that looms on the horizon is access to water. The agave can survive a drought — it’s a hardy plant. Hell, I have one growing in my backyard in Chicago. But you need water for fermentation. You need water for your workers to drink. You need water so that there can be farming in your town, so that there is food for you and your workers to eat. My friends in Minas devised a system for catching the rain waters and keeping them in reserve. You can read about that on the S.A.C.R.E.D. website. But my friend Amando, in Santa Maria Ixcatlan, tells me that last year they didn’t get nearly enough rain. He worries that his town will suffer from drought this coming year. We’re going to start funding for his water project in the near future, but it’s not going to protect him and his town from the drought that is very likely coming — you need two or three years to build up those reserves before you are protected.

PQ: How can our readers support your work?

Lou: To get back to the question you asked at the beginning, Peter, S.A.C.R.E.D. isn’t really an organization. It’s just the name that my wife Connie and I use when we’re raising money for the projects we support in Mexico. So we don’t take donations. Instead, we direct donations to the projects we support.

Anyone wanting to contribute to these projects, they can do so in a couple of ways:

To help fund the library in Santa Catarina Minas, go to the S.A.C.R.E.D. website and you’ll see a PayPal button. The donations you make through that button go directly to the account in Mexico that Sabra Dios set up to fund the library.

Planting Agave for Earth Day

Anyone interested in libraries in Mexico should also look at Sikanda, a nonprofit that builds libraries and greenhouses in the communities that have sprung up around the landfill sites surrounding Oaxaca City. They toured me around a couple of their projects earlier this year, and it was really inspirational to see these children, living a literal stone’s throw away from a garbage dump, excited about reading books.

Anyone interested in funding the greenhouse project or the water reserves, we expect to have the same kind of PayPal button set up by early December. In the meantime, sign up to our mailing list so you can join us for tastings of the rare agave spirits we bring back from Mexico. Most of these events are in Chicago or Wisconsin, but we’ve also held tastings in Scotland and London, and if enough people sign up in, say, Louisville or Vermont or wherever, I’m always happy to travel to preach the gospel of agave.

When we do these events, 100% of the money you pay to attend goes directly to the projects we support. We don’t keep a dime. Each event costs us money out of our own pocket; we pay for the spirits that you drink, usually for transportation, and there are always incidental costs. But it usually comes in at less than a hundred dollars, and the way we look at it is, if Graciela or Lalo called us and asked for a donation of $100, we’d make it. Instead of doing that, we’re turning that hundred-dollar donation into $1,000 by sharing the spirits with more people.

I’m also always happy to point people to my connections in these towns, or have them join me on one of my frequent trips to Oaxaca. The only rule is that they have to promise to leave at least $200 in these towns.

Lou, preparing for the Tres Reyes parade. You can join him if you’d like.

PQ : Thanks so much, Lou! This has been really interesting, a veritable master class, and full of great information about agave and the people whose lives depend on it. Are there any other points you’d like to share before we say adios?

Lou: Thank you, Peter! And sorry if I rambled. But not completely sorry, obviously, because here are three more things I want to share:

- If you’re drinking agave spirits (mezcal, raicilla, tequila, whatever) in a cocktail, ask for a small taste of the spirit on the side, to help you identify what flavors in that cocktail are attributable to the agave. My hope is that the bartender will, at that point, confess that they are using an inexpensive spirit to make the cocktail, and invite you to instead taste a quality mezcal or raicilla on the side.

- Some time in the next few months, Dark Matter Coffee will be offering roasted coffee beans that have been infused with agave spirits that we brought back from Mexico. A portion of each bag sale will go to support our various projects. If you’re a coffee fan, sign up on our mailing list to be alerted when this project is live.

- We’re doing a similar project with Roots Chocolates. They’ll be releasing a selection of agave spirit-infused truffles, and a portion of each sale will go to support our various projects. If you’re a chocolate fan, sign up on our mailing list to be alerted when this project is live.

Salud, Peter! Hope to see you again soon!

Agave sprouts at the greenhouse in Santa Catarina Minas — planning 20 years ahead!

Recent Articles by Peter Reinhart

- Howard Brownstein on Turnaround and Crisis Management

- Randy Clemens and Forest Farming in Uruguay — The Back to The Earth Movement is Back!

- It’s not too late to chase your dreams: “Pizza From the Heart” A New Book by Paulie and Mary Ann Gee

- Kyle Ahlgren on the Artisan Baking Center Online Classes (and a special offer)

- Multi-James Beard Nominee Cathy Whims of Portland’s Nostrana and her Brand New Book

- Pizza Quest: KID, Manhattan’s New Slice Cafe, with Chefs Ian Coogan and Max Blackman-Gentile

Comments

Add Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Agave Quest! Peter/Lou – what a great interview! Let’s hope the universe has plans for Pizza Quest to take a trip to Oaxaca!